Cervicogenic dizziness

Introduction

Dizziness and unsteadiness are the most common symptoms associated with neck pain, especially after a whiplash injury. The incidence of pseudo-vertiginous symptoms (such as vertigo, dizziness, unsteadiness, light-headedness, imbalance or instability) is very high in this type of patients, ranging between 40 and 85%. Pseudo-vertiginous symptoms can have a significant emotional impact and can be linked to anxiety, depression and fear-avoidance behaviours, which can have detrimental effects on prognosis.

Symptoms can be very varied in patients with neck pain, and may include dizziness, light-headedness, unsteadiness, nausea and blurred vision. They can be accompanied by several objective signs of sensorimotor control dysfunction such as altered cervical kinaesthetic sense, altered neck motor control patterns, altered standing balance and altered oculomotor and neck coordination.

Patients who suffer from dizziness can be classified into different subgroups based on different characteristics. Cervicogenic dizziness is one of the possible causes of dizziness. It has been defined as an a specific sensation of changed spatial orientation and disequilibrium as a consequence of a proprioceptive disorder of the cervical afferents. It occurs with certain positions and movements of the cervical spine and can be accompanied with a stiff or painful feeling in the neck. At this moment there are no diagnostic tests available to state that the dizziness of the patient has a cervicogenic origin. It’s a diagnosis of exclusion which means that other causes of dizziness have to be excluded first.

Dizziness terminology

Vertigo can be described as a false sensation of movement that the subject experiences in relation to the environment or vice versa. This type of true vertigo has its origin in the vestibular system and should be differentiated from dizziness or pseudo-vertigos of different aetiology.

It is classified as either peripheral vertigo, when the alteration occurs in the terminal organs of the vestibular system (utricle, saccule, semicircular canals and vestibular portion of the eighth cranial nerve), or central vertigo, when the alteration is located in the vestibular nuclei, cerebellum, perihypoglossal nucleus, and its different interconnecting tracts in the central nervous system (CNS). In 85% of people presenting with vertigo, the origin is peripheral, with the remaining 15% being central.

Dizziness is a more ambiguous term that is described as a subjective sensation of unsteadiness with no objective loss of balance. The patient reports a feeling of unsteadiness, swaying or weakness, sometimes accompanied by nausea.29 While the aetiology of vertigo is vestibular, the aetiology of dizziness is very diverse.30 It can be a characteristic symptom of an alteration of the visual system, an alteration of the parietal and temporal lobes, the cerebellum, fatigue, stress, etc., as well as dysfunction or pathology of the cervical spine.

Imbalance is an objective loss of stability, with no perception of movement. It is usually the consequence of an alteration in the integration between sensory input and motor responses. This symptom appears while standing and walking, and is absent when sitting or lying down. Severe imbalance in a younger patient usually indicates a central pathology, in elderly patients it should be considered a normal response associated with age.

Cervicogenic Dizziness

Cervicogenic dizziness (CD) has been defined by Furman and Cass as ‘a non-specific sensation of altered orientation in space and disequilibrium originating from abnormal afferent activity from the neck’.

The pseudo-vertiginous sensations associated with cervicogenic dizziness are the consequence of a conflict with the information gathered by different postural sensory systems. The alteration of the afferent information of the deep cervical muscles and the cervical articular proprioceptors is the pathophysiological basis of CD.

There is a general consensus that acknowledges that patients with cervical pathology may experience pseudo-vertiginous symptoms. When reported these symptoms should be investigated to confirm their relationship with the cervical spine or if they are of other origin, where they may need to be referred to a medical practitioner for further investigation.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of cervicogenic dizziness should establish a correlation between dizziness and the cervical spine, excluding a vestibular disorder and a neurovascular injury, using the subject’s previous history, the clinical assessment of cervical musculoskeletal and relevant sensorimotor impairments and the use of vestibular functional tests. The primary criteria for CD is that it must be concluded that a subject suffers from CD only when the other pathologies have been ruled out.

Subjective Assessment

The sensation of dizziness is specific to the person and type of condition. The most common sensations expressed by patients suffering from dizziness and balance disorders are:

- “The room spins, I feel nauseous and am sick.”

- “I feel constantly unsteady.”

- “Feeling lightheaded “but not euphoric” despite the fact that I never drink.”

- “When I lean forward, I feel like everything is spinning and I have to hold onto something.”

- “If I lean my head back I feel like I’m going to faint.”

- “I feel constantly unsteady when I walk.”

- “Suddenly I felt pressure and ringing in my ear and I became dizzy.”

- “When I walk it feels like I’m sinking into the ground.”

- “When I turn my head too fast, my vision blurs.”

- “I suddenly had stomach pain and nausea, I got up and I was sick; the room was spinning. I thought I had a stomach bug.”

- “It’s like I am constantly seasick.”

- “It’s like being shoved sideways and I lose my balance.”

- “I stagger when I walk.”

A patient with CD reports a subjective sensation of imbalance, and not the rotatory vertigo characteristic of vestibular vertigo. The symptoms of CD can be associated with subjective visual sensations like blurred vision and focusing difficulties. There should also be a time relationship between the onset of the CD and other neck symptoms.

Rule out VBI

Dizziness is the most common complaint associated with vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI). VBI is an uncommon presenting condition but when dizziness is present before proceeding with physiotherapy management you must rule out VBI by assessing for the following symptoms. The presence of one of these symptoms is enough to warrant caution and further investigation.

- 5D’s

- Dizziness

- Diplopia, blurred vision or transient hemianopia

- Drop attacks (loss of power or consciousness)

- Dysphagia (problems swallowing)

- Dysarthria (problems speaking)

- 3 N’s

- Nystagmus

- Nausea or vomitting

- Other neurological symptoms

- 5 others

- Light headiness or fainting

- Disorientation or anxiety

- Disturbances in the ears – tinnitus

- Pallor, tremors, sweating

- Fascial paraesthesia or anaesthesia.

Objective testing

Examination of the cervical region

The assessment of CD is complex, since there is no single specific and conclusive diagnostic test. No one test alone can diagnose CD, but that clinical reasoning of the findings in a cluster of tests, associated with the patient’s subjective reports and cervical musculoskeletal impairments, is most useful for differential diagnosis of CD. In the assessment it is necessary to consider the subjective examination in conjunction with findings of cervical musculoskeletal and sensorimotor dysfunction. A normal cervical examination can be performed. Any dizziness reported in the cervical assessment indicates the need for further investigation

Vertebral Artery Test

The vertebral artery test is used to test the vertebral artery blood flow, searching for symptoms of vertebral artery insufficiency and disease.

Cervical position sense

Performance: The patient sits in front of a wall on a distance of 90cm with a laser attached on a hairband. The starting point of the laser is marked on the wall. The patient performs 1D head motions with the eyes closed and tries to reproduce his neutral head position.

Assessment: Measure the distance between the starting point and the point where the laser stops after the head movement. The critical distance is 7cm. This is also called the ‘joint positioning error’ (JPE).

Romberg test

Performance: The patient stands upright with both feet together. First the test is performed with the eyes open, then with the eyes closed.

Assessment: Check if the patient gets dizzy or looses his equilibrium with the eyes open and/or closed. Look for deviations, direction of deviations and influence of distraction.

Finger-pointing test

Performance: The patient sits or stands in front of the therapist. The patient has to follow with his index finger the finger of the therapist as accurately as possible without touching it.

Assessment: Assess the direction of overshoot and intention tremor.

Babinski-Weil test

Performance: The patient walks 4 or 5 steps forwards and backwards with the eyes closed and both arms stretched forward at shoulder height. This is repeated a couple of times without opening the eyes in the meantime.

Assessment: Evaluate deviations and the direction of deviations of a straight for- and backwards walking pattern. The consecutive deviations can form a typical pattern assembling a star. Compare the width of the support base (wide vs narrow) between walking with the eyes open and closed.

Nystagmus test with cervical rotation

Performance: Evaluate spontaneous nystagmus. First look at the patients eyes while the patient looks at a point in front of him at a distance of more than 2 meters. Then the presence of a spontaneous nystagmus is evaluated while the patient stares from different eye-angles, such as looking upwards or to the left.

Assessment: Check the presence of a nystagmus. Nystagmus is an involuntary, rhytmic, osscilatory eye movement. A spontaneous nystagmus is a reason for referral for specialistic examination, regardless of direction, frequency or speed.

Saccadic eye movements

Performance: The patient quickly changes his gaze from one point to another.

Assessment: Assess the presence of overshoot or undershoot of the eye movements and aberrant saccadic eye movements.

Smooth pursuit test

Performance: The patient keeps the head steady and tries to follow a slowly moving object with his eyes.

Assessment: Look for influent eye movements or saccades. Other recognisable symptoms can be provoked

Gaze stability

Performance: The patient tries to keep his eyes fixed on a stable object while the head is actively moved into different directions.

Assessment: Evaluate the impossibility to fixate and the presence of saccadic or aberrant neck movements. Other recognisable symptoms such as dizziness, blurred vision and nausea can be provoked.

Eye-head coordination

Performance: First the patient moves his eyes towards a fixed object. While keeping his gaze fixed at the object he turns his head towards the object. This can be performed into different directions: left, right, up, down,…

Assessment: Check for impossibility to dissociate eye- and head movements. Other recognisable symptoms can be provoked.

Whisper test

Performance: The test can be performed while the patient is sitting or standing. Perform the test at patient’s height. The therapist sits or stands behind the patient at arm’s length. The patient covers one ear and has to repeat the combinations that are whispered by the therapist. These are six combinations of three numbers or letters. For example: 66F, G8D, 1KL.

Assessment: The test is aberrant if the patient cannot repeat more than four (out of six) combinations

Vestibular Vertigo

Vestibular vertigo is characterised by onset is sudden that lasts minutes, hours or days, and is accompanied by vegetative manifestations and hearing symptoms. Peripheral vertigo can be differentiated from central vertigo, given that the former often has a shorter duration and it can be accompanied by hearing loss and/or tinnitus, and there are no neurological signs.

BPPV is the most common peripheral vestibular vertigo. It is characterised by a sudden onset of rotational vertigo that typically lasts between 10 and 30 seconds. It can be triggered by rolling over in bed and tilting the head back. It is characterised by its short duration, rapid fatigue, and disappearance when the position that provoked it is maintained and/or changed and the appearance each time such a position is adopted. It can cease spontaneously or after otolith repositioning manoeuvres, and it sometimes reappears after a while[2].

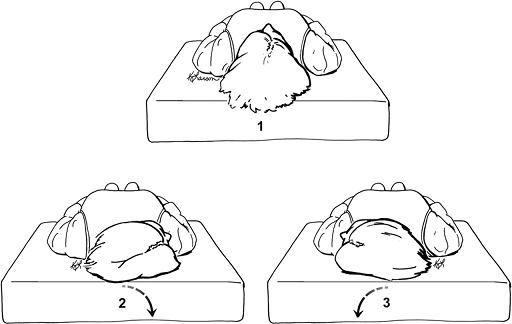

Dix-Hallpike manoeuvre

Performance: The patient takes in a long-sitting position. The head is turned 45° to one side. The therapist assists the patient quickly getting into the supine position with his head over the edge of the table in 30° of extension, maintaining the rotation. This position is maintained for at least 30 seconds. The test is repeated with the head turned to the other side.

Assessment: Note whether the test is positive for rotation of the head to the right, to the left or both. Check occurence of vertigo, presence and direction of nystagmus, latention time and time before nystagmus/vertigo has disappeared.

Roll test

Performance: This test is only performed if the Dix-Hallpike is negative but there is a strong suspicion of BBPV. The patient lies supine with his head 30° flexed. The therapist assists the patient rolling quickly to one side. The head stays in 30° of flexion. This position is maintained for at least one minute. The test is repeated with rotation to the other side.

Assessment: Occurence of vertigo, presence and direction of nystagmus, latention time and time before the nystagmus/vertigo has disappeared.